And for some women in the Black church, modest dressing and legalistic codes became necessary for their very survival. Hips and breasts and hair and bottoms were the subject of unwelcome touches, jokes, “evidence” of sexual prowess, and surveillance. And whether in their workplaces or in their own homes, Black women’s bodies were the constant subject of scrutiny. And through it all, they faced sexual abuse, accusations of hypersexuality, and other forms of sexual trauma. They had toiled in fields and in factories.

These women had worked in other people’s kitchens, homes, and laundromats to provide for their families. And I discovered facts that challenged my simplistic understanding of their theologies. I started reading history that centered Black women’s lived experiences. I started paying attention to the stories of the women raising me at home and in the church. “I started paying attention to that source material. How they understand God and holiness and modesty is rooted both in the Word and in the world. But reading Delores Williams helped me to understand that Black women are also pulling theological source material from their own lives and not just from the Christian scripture.

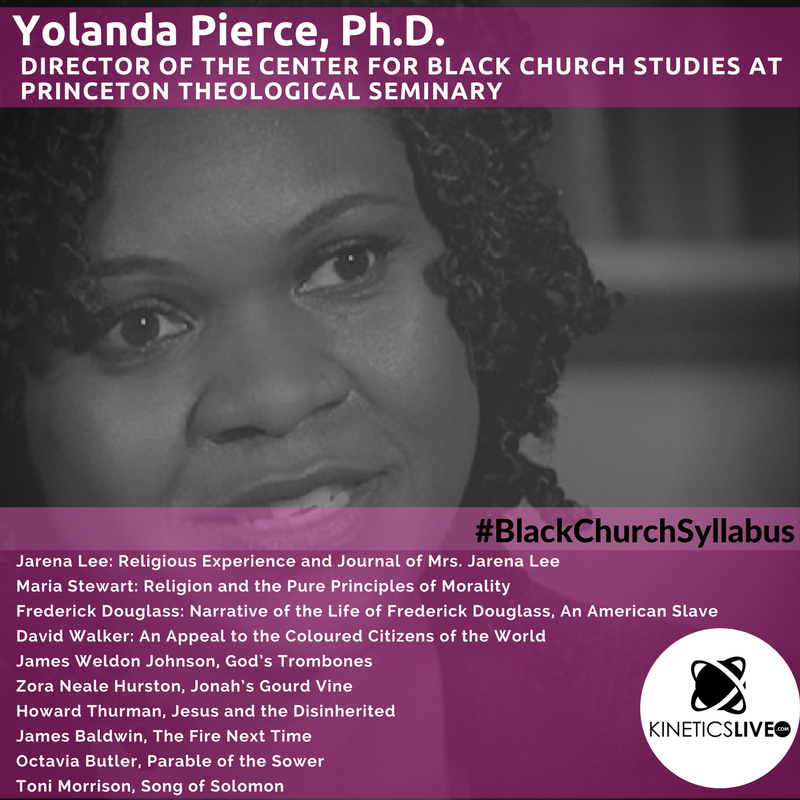

We were drilled in scriptures about the wages of sin, lest we stumble and backslide. Mother Johnson would quote 1 Corinthians 11:5, reminding me that “every woman that prayeth or prophesieth with her head uncovered dishonoureth her head.” There were countless Bible study lessons about the Proverbs 31 woman: her modesty, her usefulness, her prioritizing of care for the family. “I had spent most of my life under the assumption that these Black church women were engaged in simple hermeneutics- specifically, a literalist reading of the biblical text. This CJ blog series “Rooted: Elders, Ancestors, and Collective Memory” continues with an entry from our Masterclass faculty Dr.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)